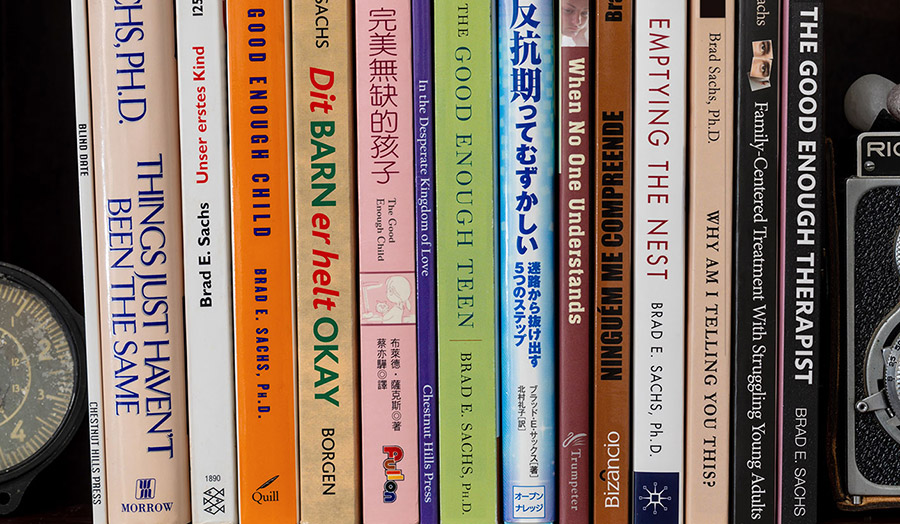

I am a best-selling, award-winning author who has published 10 books, some for general readership and others for professional readership. Many have been translated into multiple languages.

I write because it helps me to understand what I have learned from my patients, and because I want to share those lessons with a wider audience.

The Good Enough Teen

Raising Adolescents with Love and Acceptance (Despite How Impossible They Can Be)

(HarperCollins)

When No One Understands

Letters to a Teenager on Life, Loss, and the Hard Road to Adulthood

(Shambhala)

Things Just Haven't Been the Same

Making the Transition from Marriage to Parenthood

(William Morrow)

Family-Centered Treatment With Struggling Young Adults

A Clinician's Guide to the Transition From Adolescence to Autonomy

(Chestnut Hills Press)